The Cool Course Catalog

April 17, 2015

Cool Course Catalog

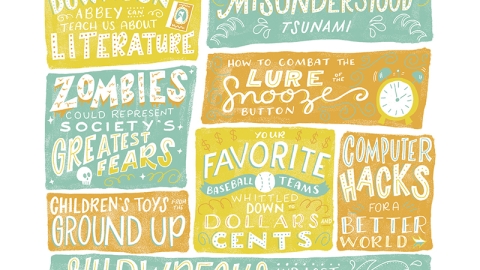

Every course at Bucknell is designed to help students think in new and nuanced ways. Professors challenge students to tackle difficult problems, to find unexpected ways to understand the world around them and to re-evaluate the ways they live their lives.

And every year, a handful of courses offers particularly novel viewpoints on the world. They link pop culture and great literature, connect campus-bound students with swashbuckling worldwide adventures and address today’s most pressing technological problems with time-tested principles. They’re the courses that make us wish, if only for a moment, that we could be students again.

We talked to professors who teach eight of these audit-worthy courses to discover the compelling details that bring these classes to life.

What a Hack

COURSE: Computer and Network Security

TAUGHT BY: Professor L. Felipe Perrone, computer science

There’s hardly a moment in our lives these days when we’re not benefiting from — or exposed to the failings of — computer and network security. Whether we’re punching in passwords on our smartphones, swiping credit cards at stores or reading the latest celebrity dirt released to the world by a hacker, we all rely on robust security systems to keep our most confidential information safe.

In Felipe Perrone’s course, students learn how to protect computer systems, in part by studying how to break into them. In one section of the course, teams of students get their own computers to maintain, equipped with an easily hackable “plain vanilla” Linux installation. They learn to use security audit tools to assess the vulnerabilities of their machines and identify any holes that need to be patched.

Then they turn over their hard work to a sinister force: another team in the class that is charged with hacking the system. Their classmates exploit any weaknesses they find in the system to reveal its contents. “The point is not really to learn to hack,” explains Perrone. “The point is to learn to cope with a hostile environment.”

That hostile environment is anything but theoretical. The much-publicized 2013 Target breach cost the retailer more than $148 million; the more recent Sony hack has had real geopolitical consequences.

But even as students learn to execute some of the most common hacks — forging emails, for example, and creating “buffer overflows” that can make systems misbehave — Perrone nudges them to use their newfound skills in beneficial, rather than harmful ways. “There’s something called ‘white hat’ hacking in which people are hired to hack organizations that want their systems to be investigated for vulnerabilities,” he says.

Ultimately, Perrone wants to teach students to analyze the strengths of all kinds of security systems — whether they’re protecting data, money or homes. “I want students to understand the safety, the likelihood of failure and the risk of misuse for any system around them,” he says.

Here Be Monsters

COURSE: Zombies of Capitalism

TAUGHT BY: Professor Clare Sammells, anthropology

Zombie flicks often suffer a reputation for being as mindless as the monsters they portray. But in Clare Sammells’ course, closer study reveals that the stories that propel these brain-gobbling baddies help illuminate society’s greatest anxieties — as well as some of its most deeply held desires.

In Haitian folklore, for example, zombies are not brainless, cannibalistic monsters: They’re people who’ve had their souls stolen, often by witches. The witches enslave these people, controlling their every move. But Haitian zombies don’t eat people, and they’re not dangerous to others. In a way, says Sammells, these zombies symbolize fears of slavery and lost humanity. “The scary part about these zombies is that you might become one, not that you might run into one,” says Sammells.

Similarly, some zombies in contemporary American films tackle the deep anxieties that many have experienced in today’s economy. “We live at a time when a lot of people are unemployed, and when there are increasing disparities between wealthy and poor. Zombie movies often address exactly those concerns,” says Sammells. Anyone who’s ever been doggedly chased by a debt collector or felt eaten alive by monthly mortgage payments can certainly relate.

But it isn’t all bad. Zombie-based tales also can offer the hope of wiping the slate clean — an idea illustrated in the show The Walking Dead. A zombie apocalypse might be unpleasant, sure, but it also allows you to slough off everything that’s tethered you to your current position in the world, whether it’s untenable credit card bills or all the mistakes that have burdened you in your life. “There’s an element of starting over,” says Sammells. “You won’t have your student loan debt, and you can move into the best house on the block — as long as you clear it of the undead. You can re-create yourself.”

Sunken Treasures

COURSE: Ancient Ships and Seafaring

TAUGHT BY: Professor Kris Trego, classics & ancient Mediterranean studies

Archaeologists are always trying to find better ways to peer into the past to understand cultures that preceded ours. For underwater archaeologist Kris Trego, there are few ways to do this more fascinating than exploring millennia-old shipwrecks.

The thrill of the search is undeniable. Explorers dive hundreds of feet beneath the ocean’s surface to explore ancient shipwrecks, and their discoveries can be breathtaking. “Some ships are almost like time capsules,” Trego explains. “Pottery can be completely intact and may still have its contents. It’s possible to find sprigs of herbs and fish netting.” Years ago, researchers even discovered an analog computer that predicted astronomical patterns, known as the Antikythera mechanism, in an ancient shipwreck off a Greek island.

For Trego, who studies ancient Greek and Roman societies, these shipwrecks offer a fuller picture of a world that we often see only through the keyhole provided by written works of the literate elite. Ship discoveries, meanwhile, can help scientists understand the details of daily life (what sailors ate, for example) or ancient technologies (such as how ships were constructed).

As students explore these new worlds, they quickly see that they must connect archaeology to countless other disciplines. They learn from the oceanographers who chart where ships lie, the chemists who analyze metals found at excavation sites and the lawyers who decipher the rule of law in international waters. “This is a truly interdisciplinary field,” says Trego. “We need historians and classicists and experts in scientific analysis of material remains to ask and answer the questions brought up by a single ship. I hope it teaches students to think about the ways we all must think beyond our own disciplines.”

How the World Changes in an Instant

COURSE: When Rocks Attack

TAUGHT BY: Professor Andy Fornadel, geology

Many of the changes our planet has undergone seem pretty slow-paced when compared to human-scale events. It can take millions of years for a mountain to form or for a river to carve out a canyon, for example.

But natural disasters can transform the Earth — and the lives of its inhabitants — as quickly as a lightning strike. Lava flows from active volcanoes can wipe out towns and earthquakes can decimate entire regions. A meteor impact has the potential to blot out entire species.

Andy Fornadel’s course doesn’t just focus on the science that explains such events. It also examines the human impact of these dramatic transformations. Often, he says, he has to start by correcting common misperceptions about natural disasters fostered by movies and television. “People often think of tsunamis as a beach wave — like the one you might see a surfer on — but scaled up a couple hundred feet,” he says. “It actually looks like a very rapid rise in sea level that can last for 12 to 18 hours.”

While the duration of natural disasters might be relatively short, the consequences reverberate for much longer. A tsunami that hits a coastal village floods out buildings and demolishes infrastructure. “On less protected islands, all that water can remove areas of the beach completely,” says Fornadel. “After a tsunami hits, there literally might be nothing left — not even land to build a hotel on.”

The course also examines how poorer areas often get hit harder by natural disasters than do more affluent areas. The major earthquake that hit Haiti in 2010, for example, was incredibly destructive because it struck an impoverished area where buildings had not been designed to withstand a major quake. The area has since struggled to recover, because the government and local residents have fewer resources with which to rebuild. “I really want students to think outside their own bubble,” says Fornadel. “I want them to deeply understand the societal effect that these events have.”

When Television and Literature Unite

COURSE: Literature of Downton Abbey

TAUGHT BY: Professor Erica Delsandro, women’s and gender studies

For even the most dedicated English student, reading early 20th-century British novels can feel like exploring exceptionally unfamiliar territory. Novels such as Rebecca West’s Return of the Soldier and Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited feature vast estates, clear upper and domestic classes and the complicated politics of World War I, which can make the very human stories they tell seem more distant than they actually are.

But Erica Delsandro found a way to breathe new life into these stories for her students: showing clips of Downton Abbey. “Students typically don’t have a detailed image in their mind of this period, so the show gives them an atmosphere and some reference points for imagining the characters and their interactions in novels, particularly when it comes to social class,” she says.

For example, students often assume that the upper class was always very conservative and that the domestic class was quite progressive — but Downton showcases the fact that there often was far more fluidity in political attitudes. Servants could be just as, if not more conservative than the upstairs family. When students see those attitudes play out on screen, they can more readily relate them to the novels they’re reading.

The class also reads Jean Rhys’ Voyage in the Dark, a novel about a woman who goes to London with dreams of becoming a chorus girl, but ultimately finds herself living as a prostitute and getting pregnant. “I think that novel would have been just a picture of a specific character for the students, except we were able to connect it to a plotline in Downton in which a maid becomes pregnant and is forced out (because her pregnancy tarnished the estate’s reputation) and must work as a prostitute to keep her baby.”

And while the focus of the class is on literature, Delsandro says she was surprised by the way students became more critical consumers of the television they were watching. “It wasn’t just that they were thinking more about Downton Abbey, but about any media that represented past eras,” she says. “It became more than just entertainment.”

The Cost of a Game

COURSE: Sports Economics

TAUGHT BY: Professor Greg Krohn, economics

Talk to any professional athlete about winning teams and losing teams, and you’ll probably hear platitudes about taking things one game at a time and the power of team chemistry. But study the numbers, and you’ll discover a story that centers on cold, hard cash.

It turns out that simple economic models can help explain much of a team’s behavior, from the players an owner signs to the team’s success on the field, says Greg Krohn. Because teams in larger cities can tap into a larger group of affluent television viewers and stadium visitors than their small-market counterparts can, they’ll always have the incentive to spend more on the talented players who lead winning teams. That incentive structure can create a competitive imbalance that helps explain why some of the perennial big-market winners, like the New York Yankees, continue to dominate, while small-market teams, like the Minnesota Twins, struggle on.

In the course, the students examine an array of policies that leagues have put into place to figuratively level the playing field, including drafts that give losing teams the first pick of young talent, reserve clauses that assign the rights to a player to a particular team and revenue-sharing agreements that give smaller teams more financial clout. For the most part, Krohn says, these policies have fallen flat. “For example, years ago, the Pittsburgh Pirates and the then-Florida Marlins received lots of revenue-sharing money, but they kept their payrolls low. It’s rational behavior for profit-maximizing team owners — the owners were just pocketing that extra money.” More promising approaches, says Krohn, combine revenue sharing with salary-cap and salary-floor policies that require teams to spend within certain constraints.

Krohn says that some students are disappointed to see their passion for a team reduced to dollars and cents, but others love the nuance an economic perspective provides. “I invite students to look at professional sports in a new way, and to look at the evidence,” he says. “I hope they consider these ideas seriously.”

Engineering Child’s Play

COURSE: Fundamentals of Biomedical Signals and Systems

TAUGHT BY: Professor Joe Tranquillo, biomedical & electrical engineering

When you press your finger to the “q” on a keyboard and the letter appears on your computer screen, you’ve experienced the way a very simple mechanical signal (the pressure of your finger on a key) gets sent through a system and creates a new output (specific pixels on a screen).

To study signals and systems in the classroom, professors have long relied on theoretical, and often brutally difficult, mathematics. But Joe Tranquillo wants his students to have more than just an intellectual understanding of these concepts. He wants students to put these ideas into action by building real products that could have a meaningful impact on the world.

This past fall, Tranquillo used a signals-and-systems framework to have his students design and create children’s games and toys. Students formed three-person teams to develop hardware, software and sensors for real products.

One team developed a remote-control car driven not with a joystick, but with a glove that tracked users’ finger movements. It wasn’t simply a new way to think about toys, says Tranquillo. “Something like this could be used for physical therapy for kids who need to develop more dexterity in their hands,” he says. “They get to see real feedback, live, as they drive a car around.”

Indeed, some students have gotten so excited about their projects that they’re taking them beyond the classroom. One group developed a game that they may ultimately launch via a Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign.

But the real benefit is to the students themselves, who have performed significantly better on Tranquillo’s tests than peers who didn’t develop a project, and who are ready for the next steps in both the classroom and their careers. “Unlike most courses, this isn’t about studying a topic, doing the homework and taking a test,” says Tranquillo. “This shows them that there’s not one specific path to success. They have to figure out what they’re going to make and what they’re going to learn.”

Binge is the New Black

COURSE: Cognitive Control

TAUGHT BY: Professor Agnes Jasinska, psychology

If you’ve ever hit the snooze button after promising yourself you’d get up the moment your alarm went off, checked Facebook instead of dealing with a knotty problem at work or binge-watched House of Cards late into the night despite the regrets you knew you’d feel the next day, you’ve wrestled with the problem of cognitive control.

It’s this concept that Agnes Jasinska and her students study closely, through both academic reading and observation of their own experiences. “This class stimulates students’ curiosity about how we accomplish cognitive control and how it works in the brain. But I also want them to pair that with a scientist’s mindset, which means critical thinking, rigorous use of the scientific method and careful weighing of arguments and evidence on both sides,” explains Jasinska.

It turns out that tamping down our worst impulses, or persevering when the going gets tough, is about much more than simply “trying harder.” Cognitive control stems from complex brain processes, and like any other brain process, it is undermined by stress, anxiety, fatigue or lack of sleep. That said, many scientists believe we can improve our cognitive control simply by using it in daily life, just as we can strengthen our muscles by going to the gym — as well as through changing our environment (placing that alarm clock across the room) and paying close attention to what makes us slip up in the first place (that pesky Netflix feature that plays the next episode of a show without us touching a button).

Cognitive control is a relatively new area of study for psychologists and neuroscientists, and the research is far from settled. That’s why Jasinska requires her students to read and think deeply about research and compare its findings to their own cognitive control experiences, which they record in a journal. They may see nuances that are ripe for future research and recognize that science is far more than just a collection of facts. “I hope students learn that science is a work in progress,” she says, “and that critical thinking and novel, creative ideas are essential to advancing our knowledge.”

Erin Peterson is a freelance writer living and working in Minneapolis, Minn.