Bucknell Researchers First to Document Firefly Pheromone

March 17, 2023

Anqi Zang '23 and other Bucknell students collect fireflies at the University's Cowan Retreat Center. Photo by Emily Paine, Communications

While it is well known that most firefly species communicate in mating through blinking patterns at night, winter fireflies — or "dark" fireflies — have lost the ability to light. Without having the advantage of a visual cue, researchers from Bucknell University, Middlebury College and the University of California, Riverside have teamed up to successfully discover that these dark fireflies mate using a pheromone — the first pheromone ever identified for fireflies.

Bucknell Professor Sarah Lower, biology, is lead author of the study, which also includes Professor Doug Collins, chemistry; and biology students Hannah Holmes ’23 and Carol Zheng ’24. Former Bucknell biology professor Greg Pask, now an assistant professor of biology at Middlebury, was also among the researchers who published their findings this week in the Journal of Chemical Ecology.

Professor Sarah Lower, biology. Photo by Carla Long

"We've identified the exact molecule that is a sex-attracting pheromone in the winter firefly that is actually out and active in the winter months across North America from Mexico to Canada," says Lower. "In field trials, we utilized the chemical we extracted, and, during their peak mating season, which is coming up in May, masses of male fireflies were attracted to the sample."

The finding opens the door to a greater understanding of fireflies in general, especially since most people believe they're a backyard summertime staple. The winter firefly, however, emerges in September and can be found only with a keen eye, since they don't light up. Because they're a close relative to the light-producing Eastern firefly, the research will help scientists understand how new modes of communication arise and develop.

"They [winter fireflies] don't really have any other way of finding each other. They’re dispersed in the forest and, somehow, have to come together to make the next generation," Lower says. "This is the way."

The Bucknell researchers put winter fireflies in glass containers and passed very clean air through that jar for four to five days in order to collect the gaseous pheromone samples.

"We think the pheromone is secreted in the waxy film on their backs and evaporated out of that film," Collins says. "Males come flying from far away to find this signal."

Professor Doug Collins, chemistry. Photo by Emily Paine, Communications

After collecting the samples, they sent them to their collaborators at University of California, Riverside — Kyle Arriola, a chemistry doctoral candidate in entomology; and Sean Halloran, an entomology research associate — who used more specialized equipment to not only identify the exact chemical structure of the pheromone, but to show how it activates a response in firefly antennae.

Antenna analysis is where Pask's expertise in neurophysiology played a key role.

"His [Pask's] speciality is chemical sensing in insects. He and his student Daphne Halley used scanning electron microscopy to identify the specific hair on the firefly antenna that identifies this pheromone," Lower says. "He was able to analyze that hair as the pheromone passed over it. He found a specific neuron that expresses a specific smell receptor in the firefly antenna that detects that specific pheromone."

Once the specific pheromone was identified, the Bucknell researchers deployed it in the field and attracted masses of male fireflies with it during peak mating season in April and May.

Both Bucknell student researchers found the work to be enlightening.

"Doing the research was pretty mind-blowing," Zheng says. "I didn't know there was a firefly that didn't have a light, and there's actually a pheromone that females use to attract males to mate with them. The educational opportunities are wonderful here."

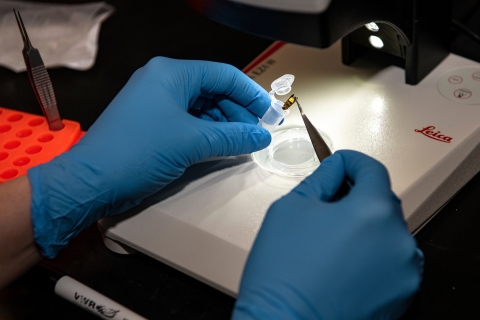

Lower conducts analysis on a firefly. Photo by Emily Paine, Communications

This is the first paper published from a $642,000 National Science Foundation grant awarded last year to Lower and Collins for a five-year study of dark fireflies and the pheromones they produce. They are also studying potential pheromones in lighted fireflies.

"One of the applications of this work is definitely monitoring populations and potentially finding other pheromones in other species that are more rare," Lower says.

"We have yet to see any pheromone from a lighted species, but fireflies can be fickle," Collins adds. "They're very specific about the conditions when they emit this pheromone."