The Book of Love

October 24, 2014

One alumna chronicles her parents’ jazz-age romance told through their love letters and her father’s drawings.

"Slifer, you’re in love!” So pronounced Roy Clement to his friend Ken Slifer. A fairly typical tease from one young man to another, but Clement turned out to be oh-so-right.

It was the summer of 1923, just hours after Ken Slifer ’26 and Clement had arrived at the Buffalo, N.Y., home of Slifer’s Bucknell pal Rolland Dutton ’26 and become reacquainted with Rolland’s sister, Caryl — and Ken was already smitten. It was a love that would endure a lifetime: Five years later Ken wed Caryl Dutton Slifer ’27, a marriage that lasted for 63 years, until Caryl’s death in 1991. And it all began at Bucknell.

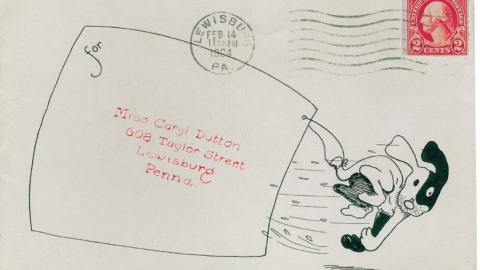

The couple wrote prolifically during their five-year courtship, even when they lived just a few blocks from each other on campus. Ken, for example, would send a formal note asking if he could visit Caryl, or inviting her to a dance. And when they parted ways for holidays, summers and Caryl’s senior year, they wrote incessantly, sometimes multiple times a day. Long-distance phone calls were prohibitively expensive back then, but postage? That was only 2 cents.

In the era of communication by texting, Instagramming and tweeting, the idea of handwritten love letters seems quaint. But these letters document the evolution of their love from the first tentative admission — Ken was the first to make the declaration — to the day before their wedding. Along the way, the letters also chronicle the 1920s: the evolution in clothing and hairstyles, the slang, popular social activities and Bucknell way back when.

Ken, a gifted artist, illustrated many of the envelopes in color: A blond with the newest hairstyle, the bob; a man in knickers and a plaid jacket, complete with cap, pipe and gold club, mouthing, “I say, old chap;” a couple dancing; an idyllic Middle Eastern skyline with minarets, full moon and palm trees. He illustrated daily life, his dreams — whatever came to mind to communicate to his dear Caryl. (Ken enjoyed a long career with Philadelphia advertising agency N.W. Ayer & Son, creators of such famous slogans as “A diamond is forever” for De Beers and “Reach out and touch someone” for AT&T.)

Ken and Caryl treasured and preserved these letters for a lifetime. When the couple was in their 40s, Ken even framed some of Caryl’s favorite illustrated envelopes as a gift to her. Caryl kept the letters boxed up tidily and stored on a shelf in her closet for decades.

Ken and Caryl’s daughter, Diane Slifer Scott ’54, recently published a full-color, illustrated book of selections from the letters. (The book was edited by fellow Bucknellian Katherine Ward '66.) The title, Flivverin’ with You, refers to a handmade Valentine that Ken sent to Caryl: a detailed drawing of a pricey Rolls Royce inscribed with the caption, “Flivverin’ with you would be jes’ like ridin’ in a Rolls Royce with anyone else.” The term “flivver” was slang back then for any small, inexpensive and old car, such as the beat-up Model T Ford driven by Ken, a vehicle the couple affectionately personified in their letters as “Liz” or “Lizzie.”

Diane, who is married to Victor Scott ’54, represents the third generation of Bucknell couples in her family, and she was followed by number four, her daughter Ellen Scott Fuqua ’78 and son-in-law Richard Fuqua ’78

After retiring, Diane set about organizing and reading the letters for her own pleasure. She planned to take notes, too, so she could write an account and pass it along to her children. “I figured I would assemble excerpts from some of the letters and copy some of the [illustrated] envelopes at Kinko’s and put it all together for the family,” Diane says. She expected the task to take a summer or so. Instead, she spent 14 years, on and off, organizing, selecting, transcribing and editing excerpts from the nearly 400 letters that had been saved. Some of the letters ran three, four, even eight pages.

“I don’t know if I might have bowed out at the beginning if I had been able to see what was ahead of me. I might have thought, ‘Holy cow! I might not live that long!’” Diane says. But she persevered, and the reward was a deepening of her understanding and appreciation of her parents. “I wanted to call them up, because I felt like they were around me all the time. The farther into the letters I got, the more involved I got in their lives and how they communicated constantly with each other, and I wanted to know more. If you can imagine knowing your mother as a teenager, what would you want to ask her? I had many questions, especially: ‘What made you know that this was the right guy?’”

As it turns out, others who read excerpts of Diane’s book-in-progress had the same fascination with the period love story, and they convinced her to self-publish the book to reach a wider audience. As one of Diane’s friends said to her: “There’s so much love in this book. We need more books about love.”

Diane witnessed the love story throughout her entire life — from humorous episodes such as when her dad greeted her mom so enthusiastically after she returned from a brief trip that he cracked her rib, to more challenging periods, such as losing a child.

Fairly early on in their correspondence, Ken, clearly head over heels, changes his salutation from “Dear Caryl” to “Caryl, Dear,” a slip that merits him a gentle — if tongue in cheek — censure from Caryl: “I must primarily reprove you for your deviation from ‘Houghton Mifflin’s’ laws of etiquette in reversing the word order of the salutation! However I shall consider forgiving you.” And to emphasize the need for formality, she closes her letter “Sincerely,” instead of the “Yours” she had signed off with in the previous one. Ken is not chastened for long before he returns to his endearing and inventive terms for Caryl, which included among many others, “beauteous damsel,” “honey girl,” “lady, love” and “my own dearest.” Eventually, Caryl relents and uses her own terms of endearment.

By summer 1925, it seems that the couple has discussed marriage. Ken’s letters refer to “our plans” and seeking the approval of his widowed mother, who gives her blessing, and in September, he gives his fraternity pin to Caryl. “My fervent hope,” Ken writes in one letter, “is that Time will build for us a sublime and lofty Faith that shall withstand petty doubts and misgivings. That sounds rather grandiloquent, honey girl, but all the sincerity I possess lies back of it. I’ve loved you so intensely and so long that I’m likely to spout ‘melodrammer’ most any time.” Elevated language? Yes, but melodrama, no, for that’s exactly the type of relationship they built, Diane says.

As the years pass, the letters begin to include stories about Ken’s work at N.W. Ayer & Son (when he got the job offer he illustrated the envelope with a man in a checked suit with harp and halo, walking on clouds), their wedding plans, their finances (they saved up their pennies — quite literally — in a honeymoon fund) and the preparations they were making for their first home. Ken’s final correspondence before the wedding expressed his desire to make the letter “so loving and eloquent that you’d treasure it always!” Caryl did.

Flivverin’ with You is available for purchase at FlivverinWithYou.com. Theresa Gawlas Medoff '85, P'13 is the associate editor of AAA World magazine and a frequent contributor to Bucknell Magazine.