Excavating a Legacy

April 6, 2017

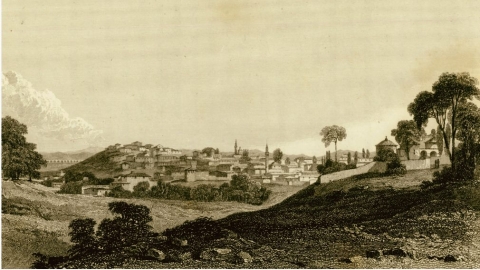

This etching of Thebes was published in 1819 by the Irish painter and archaeologist Edward Dodwell. Courtesy of The Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation

With unearthed relics chosen for a permanent museum collection, the work of the first joint Greek-American archaeological dig in Thebes, Greece, continues

Part lion and part human, the sphinx is a mythological figure that was said to guard the Greek city of Thebes by asking travelers to solve a riddle before continuing on their journey. Images of the sphinx are often found in ancient artwork, and they adorn a beautiful red figure vase that was unearthed by a group of Bucknell faculty and students, a legacy of the first joint Greek-American archaeological dig in Thebes.

The vase, which dates back to the fourth century B.C., along with Byzantine glass jewelry excavated by the team, is now on permanent display in the Archaeological Museum of Thebes. Professor Stephanie Larson, classics & ancient Mediterranean studies, says that the relics represent an important and inspiring outcome. "Bucknell is responsible for those objects existing in that space. I don't think anything as good as that will happen to me for the rest of my life in my work, because it represents everyone's blood, sweat and effort."

Larson and husband Professor Kevin Daly, classics & ancient Mediterranean studies, embarked on the dig six years ago, after receiving a $350,000 grant from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, one of the world's leading international philanthropic organizations. Although Thebes has been an important Greek city throughout history, the site of the sanctuary of Ismenian Apollo offered a rare opportunity because parts of the site remained unexplored and are not located beneath modern buildings. Daly explains that there have been only two limited excavations within its boundaries — the Greek archaeologist Antonios Keramopoulos' on the sanctuary hill from 1910 to 1917, and Nikolas Pharaklas' few additional trenches in 1967 . Neither archaeologist conducted a full exploration.

When Larson and Daly moved to Greece in 2011, they created their base from the ground up — from buying basic tools to renting and securing a storeroom to finding a place for students to live in Thebes. It was a daunting task but one that allowed them to develop strong relationships with their Greek colleagues, carry out important academic work and provide rare experience for undergraduates.

During the last six years, more than 75 Bucknell students have spent eight summer weeks learning the physical and intellectual aspects of archaeology. Students say the experience has challenged them to grow, whether by opening their minds to a new culture or translating the intense work experience to a biology lab back on campus.

Jon Hunsberger '16, a classics & ancient Mediterranean studies major, spent four summers in Greece with the team. Learning about ancient Greek material culture in contrast with today's Greece gave him a keen understanding of how history and modern culture intersect. "As I was digging, I was learning history, archaeological technique, teamwork, modern Greek language, modern Greek culture and more," he says. "My time in Greece strengthened my work ethic, connections and world experience, which I will carry into my future career."

Tyler Strobel '19 spent last summer working on the dig team during the final active excavation season. He says that the experience was invaluable. "It exposed me to the grittier side of the field. Archaeology on paper is far different from archaeology in person. As a classics major, going to Greece was priceless — from seeing the Acropolis to the Antikythera Mechanism to walking through Minoan ruins — it allowed me to integrate myself into another culture for a short time."

This connection between the past, present and future comes with great responsibility, something Larson and Daly think is important for students to learn. "You find something that's been buried for possibly thousands of years, and you're the first one to come across it," she says. "You have the responsibility to make sure that all of the details about it are recorded well. If you are not careful enough, no one will ever know the particulars of that find. It's up to you."

That's why the team has amassed more than 30,000 photographs with detailed metadata. Their workroom is filled with objects that they have unearthed, cleaned, weighed, catalogued, photographed and dated. While the eight-week excavation season is all about getting things out of the ground and recording them, study season — a time for more detailed examination — is equally important. During this next stage of the project, architects, Byzantine pottery specialists and bone experts visit sites and storerooms to share their expertise, and professional illustrators capture aspects of objects that photography misses.

The team has found pottery, jewelry and coins, among other objects. They have also explored graves, which requires removing human bones.

"We try to put them back together," Larson explains. "We're going to do some facial reconstructions with the crania from some of the graves, and we're looking for pathological diseases as well." So far, they have found leprosy, blunt trauma death, cancer, infections and genetic abnormalities.

During this final phase, Larson and Daly are part of an international team of 15 scholars who plan to write a book "that has chapters on each phase of the life of this site," she says. "It's like we're writing a biography of every decade of a life, only this place includes thousands of years as opposed to 70."