Bucknell Study: Bush Tomato Fools Bees With ‘Fake’ Female Pollen

January 5, 2022

Professor Chris Martine, biology, the David Burpee Professor of Plant Genetics and Research, co-authored a paper on his findings. Photo by Emily Paine, Communications

Consider it an act of botanical bluffing. The unisexual Australian bush tomato has both beautiful purple and yellow male and female flowers, but cross-pollination between each sex by bees is necessary for the plant's survival. Bucknell University research has now found that while both the male and female flowers produce pollen, the females somehow "fool" bees by producing a less-wholesome or "fake" pollen that looks like its male counterparts but lacks the same nutritional reward.

Since these bush tomatoes don't produce nectar, bees seek pollen in these flowers when they visit.

"That's the food source they’re looking for," says Bucknell Professor Chris Martine, biology, the David Burpee Professor of Plant Genetics and Research, who coordinated the research through his lab. "So basically, the female plants are making flowers with male organs which produce 'fake' pollen as a way to still get bees to come visit.

"The question we had is if they visit a male plant and get the 'real' pollen, and they visit a female plant and get the 'fake' stuff, are they still getting the same nutrition? And if they're not, then they're basically being fooled into visiting the female plant and not getting the same reward," he says. "It turns out that that's actually true. They're actually getting less nutrition from the female pollen, and that's pretty interesting."

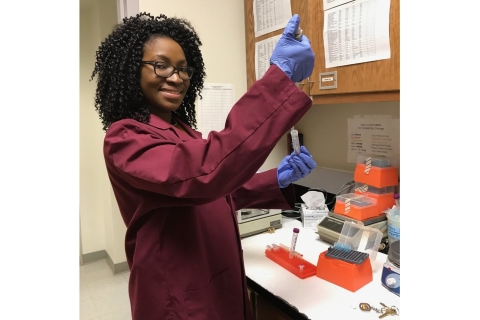

Jackie Ndem-Galbert measures "fake pollen" of Australian bush tomatoes for its potential nutritional content for bee pollinators. Photo by Jess Hall

Martine joined former Bucknell student Jackie Ndem‐Galbert '16, M '18; former visiting biology professor Jessica Hall; and Martine's previous postdoctoral fellow Angela McDonnell to find answers to that question. They authored a paper on their findings, which was published in October by the American Journal of Botany.

The researchers found higher levels of proteins and amino acids in the pollen of male flowers, producing a greater nutritive reward for bees foraging on male plants than for those on the female plants.

"I've long wondered about this question on whether the pollen is equivalent in terms of what it gives the bees, but I never had anybody that I could collaborate with to help me figure it out before," Martine says. "Then Jessica Hall was hired as a visiting professor here with a background in proteins, and we ended up co-advising Jackie. They brought this expertise to a question I had for years but couldn't answer. And with the help of Angela McDonnell, we formed this little Bucknell super team that helped figure it out."

Hall is now on the biology faculty at Ohio Dominican University; Ndem‐Galbert is pursuing her doctorate in health sciences and technology in Switzerland; and McDonnell is employed by the Negaunee Institute for Plant Conservation Science and Action at the Chicago Botanic Garden.

Martine points out that in these bush tomatoes where there are separate male and female plants, if bees don't move between both flowers, the plants won't populate.

"In this system, you have to go from a male plant with good pollen to a female plant that can receive pollen. If it doesn't go in that direction, you don't get seeds, and without them the species goes extinct," he says. "But why would a bee ever go visit those female plants if the pollen wasn't worth as much? This is the mystery we are left with at this point."

What they have learned is that the female pollen has less nutritional reward for the bee, and yet they somehow manage to lure bees in for pollination anyway. One working hypothesis is that because most of the pollen the adult female bees collect is given to their developing larvae, those moms will never know the difference — even if their babies might grow slightly differently depending on what they are provided.

All of the research was conducted using three Australian Solanum species cultivated in Bucknell's Rooke Science Building greenhouses. The researchers had collected seeds from these species during six trips to Australia over the past 15 years.

Martine hopes to continue researching how the female flowers produce their "fake" pollen and whether this now-confirmed bit of nutritional trickery results in consequences for the bees that collect and consume it.