Bucknell University Marks 150 Years of Black Excellence

September 22, 2025

For more than 150 years, Black students, faculty and staff have contributed to Bucknell University's community, mission and ethos.

This year, Bucknell celebrates the 150th anniversary of the graduation of Edward McNight Brawley, Class of 1875, the first Black student to earn a Bucknell degree. To honor this milestone, the Griot Institute for the Study of Black Lives & Cultures has spent the last year updating its timeline of Black history at Bucknell. "The University's story of Black excellence is not one of isolated achievement, but of continuous accomplishment," says Professor Cymone Fourshey, history and international relations, who serves as director of the Griot Institute. "It has been shaped by challenges alongside resilience, scholarship, cultural expression and community leadership."

Fourshey's research with student interns has framed Bucknell's Black history into distinct eras, revealing a legacy of perseverance and innovation. In celebration of our history, which dates to the University's founding years, we offer these brief windows into our past.

Early Progress (1850s–1920s)

The University's early years were marked by quiet but groundbreaking milestones. Records in Bucknell's University Archives indicate that runaway slaves traveling by way of the Underground Railroad through campus were assisted by Lucy Bliss, daughter of Justin Loomis, who served as Bucknell University President from 1858 to 1879. During his tenure, in 1867, Charles Bell, a former runaway slave, was hired to maintain Bucknell's grounds and went on to work for the institution for more than 40 years.

Charles Bell, a former runaway slave from West Virginia, was hired to maintain Bucknell’s grounds, making the University his home for more than 40 years. Photo courtesy of University Archives/Special Collections

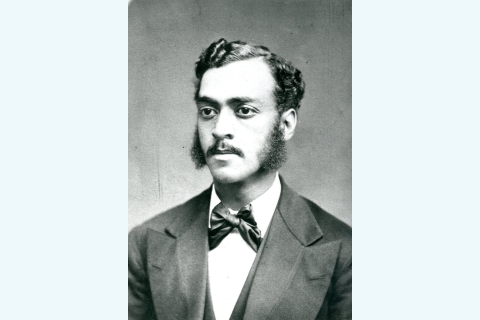

Just a few years later, in 1875, Brawley became not only Bucknell's first Black graduate to earn a bachelor's degree, but also the first at a Pennsylvania university. He also earned a master's degree from Bucknell in 1878. Brawley became a minister, religious scholar, journalist, and eventually the president of Selma University and Moore College, which he also helped establish. In the decade that followed, five more Black men graduated from Bucknell, each building on Brawley's trailblazing path.

Edward McKnight Brawley. Photo courtesy of University Archives/Special Collections

In 1924, Helen Evelyn Holmes became the first Black woman to graduate from Bucknell, and was followed by several other Black women seeking higher education. While records remain limited, these early graduates helped make Bucknell an exception among predominantly white institutions of the era.

Although the numbers remained small, these first 50 years established a foundation of Black academic excellence at a time when access to higher education was severely limited.

Integration, Leadership and Culture (1950s–1970s)

After World War II, enrollment of Black students slowly began to rise. In late 1950s and early 1960s, Black students pursued degrees in engineering while breaking barriers on campus through involvement in student organizations, sports, and on-campus housing. During this period, the University entered the broader societal dialogue, hosting influential Black voices such as Langston Hughes, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Jackie Robinson.

In 1960, Black athletes integrated the University's sports programs. While they often faced hostility from peers and the local community — like Black athletes who were barred from entering downtown establishments after championship wins — their courage laid the groundwork for greater inclusion across campus.

Seventh Street House. Photo courtesy of Bucknell Marketing & Communications

These students' experiences primed the University for a decade of transformation. A new wave of Black enrollment in the 1970s fueled cultural and social organizing as students carved their place in campus life. On April 24, 1970, the University formally named the Seventh Street House and Edwards/Amani House, which became cornerstones of belonging and inclusion for Black students.

In 1976, the Student Government Association of Bucknell Students (now known as Bucknell Student Government) elected its first Black president. By 1979, Black Greek-letter organizations — part of the Divine Nine — had established chapters on campus, strengthening student leadership. Cultural programming flourished as well, with the Black Arts Festival emerging in the 1970s as a celebration of intellectual activity, creativity, identity and resilience.

Students plan the University's annual Black Arts Fest, a celebration of Black life and culture. This group led the sixth annual event in 1977. Photo courtesy of Special Collections/University Archives

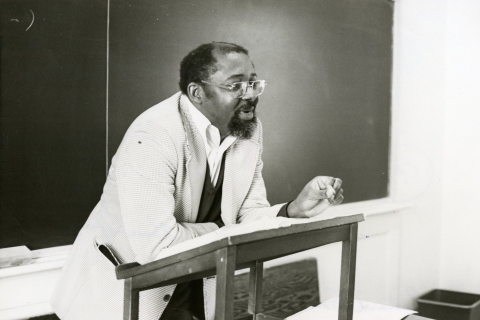

In 1971, Professor Richard Smith joined the English Department as the University's first Black tenure-track faculty member. With his wife, Yvonne, Smith fostered a community of Black intellectualism and culture at Bucknell, hosting dinners and gatherings that provided students with a vital sense of belonging and academic support. By 1978, he made history again as the first tenured Black professor.

Professor Richard Smith, English, is remembered for the deep community he and his wife, Yvonne, cultivated for Bucknell students. Photo courtesy of Special Collections/University Archives

Building Community and Institutional Support (1980s–1990s)

The momentum of the 1970s continued into the 1980s and 1990s, marked by the creation of lasting institutions and support systems for Black students.

In 1990, the University hosted its first Martin Luther King Jr. celebration, solidifying a commitment to honor civil rights legacies. Student organizations, including the National Society of Black Engineers and other affinity groups, supported academic and professional growth. By 1995, the Black Student Union — originally formed as BASE (Black Awareness Student Ensemble) — became a cornerstone of student life, ensuring representation and advocacy.

Members of the National Society of Black Engineers. Photo courtesy of Special Collections/University Archives

This period also witnessed the formal establishment of offices and programs dedicated to multicultural student support and the academic exploration of the Black experience, setting the stage for the next era of academic expansion.

Global Learning and Africana Studies (2000–present)

The new millennium ushered in an era of global connection and intellectual growth. Bucknell students gained opportunities to study abroad in Ghana and the Caribbean, expanding academic exploration to locations beyond Europe, Asia and Latin America. These new locations added opportunities for comparative studies across the Black Atlantic. On campus, new initiatives spun the first threads of what would eventually become a rich tapestry of scholarship. The Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity & Gender was established, and 2010, the University opened the Griot Institute for Africana Studies (renamed to its current title in 2019) to provide students and faculty a resource for intellectual and creative engagement with the interdisciplinary investigation of the cultures, histories, narratives, peoples, geographies and arts of Africa and the African diaspora.

Professor Jaye Austen Williams was the first Black faculty member hired in the Africana Studies Department. Photo by Emily Paine, Marketing & Communications

The most significant academic milestone was the development of the Department of Africana Studies, ensuring that Black history, culture and intellectual traditions are studied with rigor and recognition. The department, formally established in 2015, is today known as the Department of Critical Black Studies.

An Ongoing Legacy

From Edward McNight Brawley's graduation in 1875 to the academic work and community initiatives of today, each generation of Black Bucknellians built upon the courage and commitment of those before them becoming academics, artists, CEOs, entrepreneurs, political activists and leaders, and engines of social change.

The University prepares to celebrate the notable anniversary with a series of events during Homecoming Weekend. "We want our entire alumni and student community to join us as we acknowledge this milestone," says Fourshey. "The events are meant to both celebrate the accomplishments of our past and support the continued legacy of Black excellence at Bucknell, despite persistent challenges."