Student-Faculty Research Finds First Evidence of Carbon Monoxide in E-cigarettes

November 25, 2019

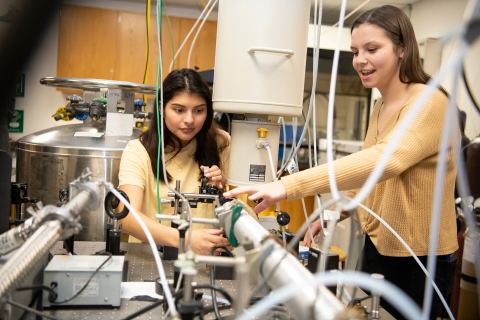

The study, headed by Jewel Cook '20, Anna Islas '20 (center) and others adds a new dimension to the debate surrounding the safety of the devices. Emily Paine, Communications

The facts are increasingly clear — e-cigarette use, or vaping, may be hazardous to your health. With U.S. health statistics linking the devices to nearly 50 deaths and more than 2,000 lung injury cases in fall 2019.

Bucknell University student and faculty researchers are now adding to the mounting evidence, with a groundbreaking study that began as an undergraduate research project. In October, the group published the first study finding that carbon monoxide (CO) can be produced when e-cigarettes are used at higher power settings.

The research on e-cigarettes was initiated three years ago by students of Bucknell and Professor Dabrina Dutcher, chemical engineering and chemistry. Together with Dutcher and Professor of Chemistry Karen Castle, Bucknell students Rileigh Casebolt '18, Jewel Cook '20, Ana Islas '20 and Carnegie Mellon University student Alyssa Brown published their findings in the journal Tobacco Control in November.

Jewel Cook ’20 (right) says the study's results have helped her convince her father to give up vaping. Emily Paine, Communications

The study's implications are hard to underestimate, and a major accomplishment for the undergraduate students, Dutcher says.

"We're the first to show the relationship with carbon monoxide as a function of the power of the e-cigarette," Dutcher says. "The study proves that we really don't know what's coming out of e-cigarettes, but we now know there are potentially harmful chemical reactions."

High Levels of Carbon Monoxide

The researchers used a high-powered laser device in Castle's lab to measure the carbon monoxide levels found at various power settings of an e-cigarette. They also tested it with a variety of flavored e-fluids.

They found carbon monoxide concentrations of over 180 parts per million (PPM) at the device's maximum 200-watt power. By comparison, the U.S. National Ambient Air Quality Standards for outdoor carbon monoxide concentrations are 9 PPM for eight hours, and 35 PPM for an hour. The current Occupational and Health Administration permissible exposure limit for carbon monoxide is 50 PPM for an eight-hour average.

For that reason, the researchers conclude that "vulnerable populations should be advised to either abstain from vaping or limit vaping to lower powers in order to minimize CO exposures."

A Student-initiated Effort

The project began as Casebolt's honors thesis project, and was picked up by Cook, Islas and Brown after she graduated. Over two years, the current students collected the data used in the study in on-campus labs.

A vaping device used in the study. Emily Paine, Communications

"I'm grateful that I was able to join a project that's super relevant, particularly since I'm very big on direct applications rather than theoretical concepts," says Islas, a chemistry major from Baltimore. "Seeing something that's so applicable and being able to quantify the danger, the carbon monoxide, helps give people hard facts that they have to digest when they are contemplating buying an e-cigarette."

Beyond sounding a warning to their peers, for Cook, the project has generated another positive, more personal result. After conducting her research, she convinced her father to stop using e-cigarettes because of what she found. She's pleased to be extending the concerning health knowledge on vaping to others through their study.

"It's very exciting just to be relevant in our research to current news making headlines," says Cook, a chemical engineering major from Croydon, Pa. "I have a lot of people texting and calling me about the reports on e-cigarettes telling me that your research needs to get out there so everybody can know what you've found."